|

| Scrapple, Eggs, and Tomatoes |

I explained as well as I could that scrapple is a member of a class of foods designed to make use of all the scraps leftover from butchering a hog. It is in essence headcheese cross polenta, formed into loaves, sliced and fried, generally served as a breakfast food.

Knowing that searching for commercial scrapple here in Oregon was probably a non-starter, I resolved silently to make her a batch so that she could taste it again for herself. Before I get into my scrapple making tale, a little backstory is in order.

While I grew up in central Virginia, my people are all from a couple hours south in Southside, the former tobacco country along the North Carolina border where scrapple was a fact of the breakfast table. Despite some hog butcherings in the family, I do not recall anyone in the family making scrapple. I do vividly remember boiling kettles of lard and the resulting crunchy bits of skin called cracklin' that adorned our cornbread. But no, scrapple making I don't remember. By the time I can remember, scrapple was something bought at the grocery store and Rapa was the family brand.

As an adult, I had migrated a couple more hours north to the very northern tip of Virginia in the Shenandoah Valley, an area that was settled largely by Germans coming around the mountains from the north from Philly and southern Pennsylvania. There in Winchester, I learned that scrapple was readily available at the deli counter of the supermarket, going by the Pennsylvania Deutsch name of Panhaas ("pan hare/rabbit" in German).

With panhaas available in bulk, I never paid too much attention to the packaged scrapple in the cold case, though I did notice two things: 1) packaged scrapple was available in two brands, Rapa and Habersett, and 2) the Pennsylvania Dutch panhaas was stiffer and contained less liver than I was used to.

Nowadays, scrapple production in the US is largely controlled by a single company, Jones Dairy Farm, that owns both Rapa and Habersett brands and recipes, as well as producing scrapple under their own label. And I believe both products are made primarily in the old Rapa factory in Delaware.

When I was a kid, Rapa was a Delaware brand out of Bridgeville that basically owned the Baltimore, DC, and Virginia markets. Further north from the Harrisburg PA area, if memory serves correctly, came the Habersett brand which ruled in the Pennsylvania market. Your scrapple allegiance, therefore, was basically a result of where you lived. People that love one brand still like to put down the other brand, but they're all good.

Back in the day, I used to see small vendors with handmade scrapple in the big markets in York, Baltimore, and Dover, but those folks seem to have gone the way of a lot of good things. Any longer, and especially where I live in Oregon, if you want handmade scrapple, you're going to have to do it yourself.

Before the scrapple tutorial, I will also point out slight variations as I know them. Panhaas tends to contain buckwheat flour in addition to cornmeal as a binder, yielding a firmer product. Further south in the Carolinas, they have livermush, which is also awesome, but focuses more on liver than does scrapple. Further west in the Ohio territory you find goetta, a similar product bound with oats. These products clearly demonstrate the early German settler diaspora in the US.

Making Scrapple

|

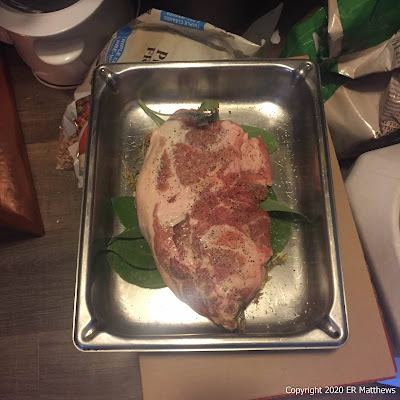

| Pork Shoulder, Sage, and Garlic |

In the restaurant days, when we had a constant supply of hogs, making scrapple was a lot easier than it is at home today. We made scrapple in the traditional style, always having a head, the neck, and some liver to use. But in all honesty, we made more headcheese and liver mousse than scrapple, just because those products were easier to move on our charcuterie boards.

While boiling is really the best way to get the meat from a head or neck bones, if you're starting with shoulder as I am forced to do at home, you might as well roast the shoulder to intensify the flavor versus boiling/stewing it. I placed a slab of shoulder on several sage sprigs and crushed cloves of garlic. I put the pan, covered in foil, in a slow oven to roast until falling apart, about three hours.

|

| Chopped Pork Shoulder |

After chilling overnight, the pork was ready to break down. I pulled all the meat off the bones, skin, and fat and chopped it pretty fine.

|

| Making the Stock |

Because I did not boil the meat, I needed to make a stock in which to cook the cornmeal. All the scraps, juices, sage, and roasted garlic went into a stock pot along with a lot more fresh sage, sprigs of thyme, parsley, red onion, lovage, leek leaves, dried arbol chiles, black pepper, bay leaves, and some fresh pork trimmings. I wish I had had some pork trotters to amp up the gelatin in the stock. Towards the end, I added four sheets of gelatin to help make up for that.

After draining the highly reduced stock, I used it to make a couple cups of cornmeal into very thick mush and then mixed in the chopped pork shoulder. I lined a mold with plastic wrap and coated the plastic wrap with pan spray to make it easy to release the set block of scrapple. In went the mush and after it cooled, I finished wrapping the mold and put it into the fridge overnight to set.

|

| Scrapple Cooking |

Inverting the mold and tugging on the plastic wrap released the block of scrapple from the mold. I then sliced the block into 3/4" slices, rolled them in seasoned flour, and fried them. For me, scrapple is all about texture, that wonderful contrast between crisp outside and almost molten inside, which is why I slice it so thick.

The trick to cooking scrapple slices is modulating the flame so that outside gets good and crisp without causing the slices to melt and fall apart in the pan. Basically, it requires a moderate flame and the patience to let a good crust develop.

So there we go: Scrapple 101. Damn was it good, but still I wish I had some pork liver to give this batch more flavor!

No comments:

Post a Comment